Walking into my garden in early spring always feels a little like stepping into a promise: the soil warming, tiny shoots pushing upward, and the anticipation of color returning after winter. In Zone 6b, those transitions are real and firm—you’ll see true signs of life from mid-April onward, and by late October, you’re already planning how to protect against the first frosts. Over the years I’ve learned that planting the right species—those adapted to survive your winter lows—makes all the difference between heartbreak and a lush, resilient garden.

I have rounded up “14 Best Plants for Gardening in Zone 6b” because I believe a carefully curated list can help even a newer gardener feel confident. Instead of trying dozens of species and watching many die off, you can start with plants known to handle cold winters and warm summers. Plus, each plant I discuss has traits that make it suited to this zone—whether that’s cold hardiness, tolerance for seasonal moisture swings, or maintenance ease.

I’ll walk you through everything: how Zone 6b’s climate works, tips for soil and frost timing, then dive deep into each of the 14 plants (spanning flowers, shrubs, vegetables, perennials, and herbs). My hope is that by the time you finish reading, you’ll already be imagining where in your yard each one might go.

Understanding Zone 6b

A. What Does “Zone 6b” Mean?

When gardeners refer to “Zone 6b,” they’re talking about a classification based on the USDA Plant Hardiness Zones, which map regions according to their average coldest winter temperatures. According to the USDA’s system, Zone 6b typically experiences minimum extreme winter temps between about –5 °F and 0 °F (roughly –20.6 °C to –17.8 °C). Those figures set a boundary: plants rated hardy to Zone 6b or lower have a better shot of surviving your winters without special protection.

It’s important to understand that these zones are averages and guidelines—not guarantees. Microclimates in your yard (warmer south-facing walls, wind channels, cold pockets) can shift success one way or another. In practice, you’ll want to see whether a plant is comfortably hardy “to 6b” rather than just barely surviving. Gardens in Zone 6 are known for supporting a wide range of perennials, shrubs, and vegetables, but the species you pick must match your conditions.

Also, keep in mind that the hardiness map is a tool, not a rulebook. It tells you which plants might survive the cold, but you still have to consider soil, drainage, sun exposure, and moisture. Even a hardy plant in poor soil or a soggy area can struggle, so using the zone rating as a screening tool (rather than a guarantee) keeps expectations realistic.

B. Zone 6b Climate Overview

In Zone 6b, you’ll experience four distinct seasons: relatively mild springs, warm summers, colorful autumns, and cold winters. The growing season is long enough (often from mid-April to mid-October) that most vegetables, perennials, and shrubs have time to flourish before frost returns. Spring may begin cool and wet, then summer brings bursts of heat, and fall tends to arrive abruptly in many places.

Frost dates are critical here. The “last frost” in spring often lands in April, and the “first frost” in autumn can come in mid to late October. This gives you a window of perhaps 180–200 days (sometimes more, depending on microclimate) to plant, grow, harvest, and rest. If you plant too early or leave frost-sensitive plants out too late, cold snaps can harm buds or leaves.

Rainfall and soil moisture patterns also matter. Winters often bring snow or freezing rain, while summers might include dry spells. Soils tend to be wetter in spring (which can suffocate roots if drainage is poor) and drier later in the season (requiring irrigation). When choosing plants, aim for those that tolerate both ends of the moisture spectrum—especially species that handle spring sogginess and some summer drought.

Tips for Successful Gardening in Zone 6b

A. Know Your Frost Dates

One of the first things I do each season is mark my “safe planting windows”—when last frost has passed and when first frost is likely to hit. I consult local extension services, historical weather data, and sometimes my own garden logs. That helps me decide when to transplant seedlings, when to sow directly, and how long I can keep summer plants out in fall. If you plant too early, late cold snaps can damage young leaves or shock transplants; too late, and your plants may not mature before frost.

A trick I’ve found useful is to stagger planting: give yourself buffer zones of a few hardy transplants when uncertain, rather than putting out all tender plants at once. Also, using cold frames or low tunnels helps you “push” the frost boundary a little. When fall arrives, having a lightweight row cover on hand can help you squeeze extra weeks of growth from certain vegetables.

Finally, a little flexibility helps — watching the forecast rather than rigid dates. If an unusually warm spring comes early, you might get away with planting sooner; if a cold snap lingers, wait one more week. The zone map gives you safe ranges; you fill in the daily decisions based on your microclimate and weather.

B. Soil Preparation

I can’t stress soil preparation enough—good plants in poor soil don’t stay good for long. First, test your soil (pH, organic matter, nutrient levels). Most plants in Zone 6b thrive when pH is near neutral (6.0–7.0), though some prefer slightly acidic or alkaline. Add compost, well-rotted manure, or organic matter to improve texture, drainage, and fertility.

If your soil is heavy clay, I mix in sand, compost, or perlite to lighten it, especially in beds meant for vegetables or shrubs. Good drainage is essential in spring’s wet periods so roots don’t suffocate. For raised beds or berms, I often “pre-mix” the soil layers with compost and good topsoil before planting.

Mulch is your friend: a 2–3-inch layer of straw, shredded leaves, or bark helps suppress weeds, regulate moisture, and moderate soil temperature. In fall, it also gives some insulation to roots. In winter, I leave mulch or mulch+leaf cover in place for plants that need a buffer against freeze-thaw cycles.

C. Watering and Mulching

In spring, your new beds may stay moist for longer, so water sparingly until the top few inches dry. Overwatering is a common mistake early in the season, especially when snowmelt or rains fill the soil. As summer warms up, check moisture deeper down (4–6 inches) rather than just surface dryness before applying water.

During heat waves, I water deeply but less frequently (e.g. soak 1–2 times per week rather than light daily watering). That encourages roots to reach deeper rather than hugging the surface. Early morning watering is my go-to—less evaporation and the foliage dries before night, reducing disease risk.

Mulch helps smooth out water needs by reducing surface evaporation and moderating temperature swings. It also breaks the impact of heavy rain so the soil isn’t compacted. In fall, I leave mulch in place (or add fresh) to protect perennials, bulbs, and shrubs from freeze-thaw cycles. In late winter, I’ll pull mulch back a little in spring to let soil warm.

D. Seasonal Garden Planning

I always try to layer my planting plan across the season so something is always thriving. In early spring, I lean into cool-season greens and root vegetables. As soon as the ground is workable, I get peas, lettuce, and radishes going. Then I shift to warm-season crops like tomatoes, peppers, and annual flowers.

Mid- and late summer is for supporting those plants (watering, staking, disease control) and prepping fall crops (like late carrots, spinach, kale). In August, I may sow a fall round of greens or root crops, especially in sheltered spots. As plants wind down, I plan my perennials or shrubs for fall planting, giving them time to establish before frost.

Winter is for dreaming and planning—order seeds, prep beds (add compost, test soil), repair your tools, and map out next year’s layout. I also monitor snowfall, check for rodent damage to crowns, and pull back snow loads if possible. Having that calendar in mind keeps me from scrambling when the first frost warning hits.

14 Best Plants for Zone 6b

Here are the 14 plants I’d personally start with in a Zone 6b garden. I’ve grouped them by type (flowers, veggies, shrubs, perennials, herbs) to help you mix and match.

A. Flowers

1. Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Black-Eyed Susans are workhorses in gardens. They bloom mid to late summer with bright yellow or golden petals around dark centers, and they tolerate heat, drought, and average soil easily. Their long blooming window and resilience make them ideal for Zone 6b beds.

They also attract pollinators—bees and butterflies love them, so if you want your garden to hum with life, this is a great inclusion. Deadheading spent blooms often gives you extra flowering time. I once had a patch of rudbeckias that bloomed from July into October with minimal fuss.

In terms of winter hardiness, Rudbeckia is reliably hardy to Zone 6 and even lower in many cases. Just leave some of the seed heads through winter if you want self-seeding (birds will thank you too) or cut them back in early spring. I cut mine back to the ground before new growth begins.

2. Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Coneflowers are a favorite of mine because they combine beauty, utility, and toughness. Their tall stems, purplish petals, and cone-shaped centers are iconic—and they hold up well to wind and heat. They’re drought tolerant once established, which is a big plus in hotter midsummers.

In addition, they’re fantastic for pollinators and beneficial insects. The seeds attract birds in fall and winter. I like letting some seed heads stay to feed goldfinches. From a design perspective, they work beautifully in mixed borders or cottage-style beds.

Winter-wise, coneflowers usually survive quite well in Zone 6b with no special protection. I sometimes mulch lightly and ensure good drainage, since soggy winters can stress even hardy perennials. In spring, I clean up dead stems and give a dose of compost for fresh growth.

3. Daylily (Hemerocallis)

Daylilies are some of the easiest perennials I’ve grown. They tolerate a wide range of soil types, sun exposures (especially full to part sun), and moisture conditions. Their flowers last a single day (hence the name), but with multiple buds per stem, you get ongoing color for weeks.

They’re nearly bulletproof. In my garden I’ve planted them in spots others shy from—rocky beds, marginal soil, edges—and they still crowned themselves as standouts in bloom season. Dividing them every few years keeps them vigorous and prevents crowding.

In winter, daylilies are hardy in Zone 6b and generally need minimal protection. I leave the foliage standing until it browns, then cut back in early spring and add mulch around the crown if winters are harsh. Their underground rhizomes are usually safe under typical winter conditions.

B. Vegetables

4. Tomatoes (Early Girl, Celebrity varieties)

Tomatoes are warm-season staples that reward patience. In Zone 6b, you’ll want to start seeds indoors about 6–8 weeks before your last expected frost (often in April). Ferry-Morse+1 Harden off the seedlings before transplanting in late spring, once nights remain reliably above freezing.

When transplanting, bury part of the stem (remove lower leaves) to encourage stronger root systems. Use cages, stakes, or trellises—this is especially important in healthier soils that encourage strong growth. Mulch around the base to retain moisture and reduce disease risk. I use straw or shredded leaves.

Pest vigilance is key. Common pests in Zone 6b include tomato hornworms, aphids, and blight. I rotate crops, keep foliage well-ventilated, and inspect leaves weekly. With proper care, you can get a robust tomato season from June through fall’s first frost.

5. Carrots (Danvers 126, Nantes varieties)

Carrots are one of those vegetables that truly thrive in cooler weather, which fits the spring and fall shoulder seasons of Zone 6b beautifully. I sow them outdoors early in spring, as soon as the soil is workable, and again in late summer for a fall crop. Sow True Seed

They prefer loose, deeply tilled soil free of stones so roots can grow straight and deep. Use fine compost or well-rotted manure, but avoid overdoing nitrogen (which encourages foliage, not root). Thin seedlings carefully so each root gets space. I’ve had batches where overcrowding led to skinny, twisted carrots.

Harvest when roots are mature but before the ground freezes. One trick: in fall, a light mulch over carrots can improve sweetness by letting cold “harden” the roots. Pull them carefully so they don’t snap, and store in a cool, moist place if you’re not eating immediately.

6. Peppers (Bell and Jalapeño varieties)

Peppers love the heat and full sun, so plant them in the warmest, sunniest spot you have. I start my pepper seeds indoors 8–10 weeks before last frost, then gradually expose them to outdoor conditions (hardening off) before transplanting. Warm soil and consistent moisture yield better fruit sets.

Spacing is important: allow at least 12–18 inches between pepper plants so air circulates around foliage and reduces disease risk. I often mulch around them to reduce weed competition and retain soil moisture. Watering deeply and consistently promotes even fruit development.

If autumn nights cool too soon, I sometimes use floating row covers or small cloches to extend the season by a few weeks. In sheltered spots, I’ve even coaxed peppers into November harvests. Just watch for early frost warnings and be ready to harvest before damage hits.

C. Shrubs

7. Hydrangea (Annabelle or Limelight)

Hydrangeas are garden stars in many climates—and in Zone 6b, some varieties like ‘Annabelle’ or ‘Limelight’ can shine beautifully. They prefer partial sun (morning sun, afternoon shade) and consistently moist soil. I plant mine with some organic matter and mulch to keep roots cool and moist.

Pruning depends on the type: for example, ‘Annabelle’ (a smooth hydrangea) blooms on new wood, so you can cut it back hard in late winter or early spring and still get blooms. Panicle types like Limelight also flower on new wood and can tolerate heavier pruning. In a tough year, pruning helps reduce stress and wind damage.

To protect buds from late spring frosts, I sometimes drape frost cloth early or avoid pruning too early. A light mulch around the base helps insulate, and if you get an unusually harsh winter, I wrap the root zone to buffer freeze-thaw cycles. Most years, though, hydrangeas do fine in 6b.

8. Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens)

Boxwoods are classic evergreens for hedges, borders, or foundation plantings. Their dense, glossy foliage provides structure even in winter. They prefer well-drained soil in part shade to full sun. I ensure they don’t sit in saturated soil—good drainage is nonnegotiable.

Winter burn and cold desiccation can be a concern, so I wind-break or shield side exposed to prevailing winds. Mulching helps protect roots, and sometimes I’ll spray a light anti-desiccant on top leaves (especially on younger shrubs) in late fall. A sturdy windbreak on the wintry side can save you heartache.

Pruning is fairly forgiving; light shaping in late spring or early summer usually suffices. Avoid heavy pruning late in the season, as new growth may not harden before winter. Over the years, my boxwoods have served as backbone structure in shady parts of the yard, holding form and color when other shrubs are bare.

9. Lilac (Syringa vulgaris)

Few shrubs deliver fragrance and bold blooms like lilac. These classic favorites do particularly well in zones that experience defined winters, since they often need chilling hours to bloom reliably. In Zone 6b, lilacs can thrive, given good sun and cold enough winters. I pick varieties that reliably bloom in my area (double check local recommendations).

They prefer full sun (at least six hours a day) and well-drained, slightly alkaline soil. I avoid planting too close to trees or structures where shade or root competition might stunt them. In winter, their dormant buds are relatively hardy, but you may want to avoid pruning too late (which can remove flower buds).

Lilacs benefit from occasional rejuvenation pruning: after flowering, I cut a few of the oldest stems to ground level to encourage fresh shoots. I also feed lightly with compost or balanced fertilizer in spring. Over the years, the strong fragrance of a lilac in bloom has been one of my garden’s most rewarding returns.

D. Perennials

10. Hosta

Hostas are shade garden champions. In Zone 6b, they reliably return each year, filling dark corners with lush foliage and, depending on the variety, fragrant spikes of blooms. They love consistently moist, rich soil and do best in areas with morning sun or dappled shade. I plant mine under trees or beside walkways to brighten shady edges.

One thing I always watch with hosta is pests—slugs, snails, and deer can take a toll. I use copper tape, diatomaceous earth, or low-impact slug traps, and sometimes fencing in especially vulnerable areas. Because hostas grow relatively slowly, protecting them early helps them bulk up faster.

In fall, I leave the leaves until they naturally brown (so the plant can feed its roots), then cut back. In winter, a light layer of mulch helps insulate the crowns, especially in spots where freeze-thaw cycles are extreme. In spring, I uncover slowly and tidy up old debris to reduce disease pressure.

11. Peony (Paeonia lactiflora)

Peonies are legendary for their longevity—they can live for decades with minimal fuss. Their large, often fragrant blossoms make them centerpiece perennials. In Zone 6b, they perform well, provided the crowns are planted at the correct depth (about 1–2 inches below soil surface) and in full sun to part sun.

They prefer well-drained soil, and when watering, I avoid wetting the crowns (water at the base). In my experience, peonies do best with a modest drink during dry midsummers but dislike overly soggy soil. Dividing every 8–10 years helps when they start to decline or get crowded.

Peonies also need good winter care—their buds are robust, but top growth should be cut back after frost. I mulch lightly (not too thickly) to protect roots. As spring arrives, tender shoots push upward. I stake or use supports for heavy blooms to prevent flop in wet weather. Over time, they become pillars in my perennial beds.

12. Sedum (Autumn Joy)

Sedum, especially varieties like ‘Autumn Joy’, is one of those perennials that looks better the more it weathers. It tolerates drought, poor soil, and sun exposure—hardly a fussy plant. In Zone 6b, sedum sits through heat, then offers color and structure through fall into early winter, even when many other plants are spent.

One of my favorite features: its flowers change tones (often from pink to bronze) as fall progresses. That gives dynamic interest late in the season when many beds are fading. It also attracts pollinators and holds up well to wind and rain.

Sedum’s roots are hardy and do well through winter. Because it’s so drought tolerant, I don’t fuss over watering once it’s established. In fall, I leave it standing so birds can feed on seedheads or I cut it back in late winter. It’s one of those “plant and forget (mostly)” perennials I often recommend to newer gardeners.

E. Herbs

13. Lavender (Munstead or Hidcote varieties)

Lavender brings fragrance, charm, and medicinal/culinary uses. In Zone 6b, not every lavender variety thrives, but Munstead and Hidcote are among the more reliably hardy ones. They require excellent drainage and high sun exposure—wet winters will be more threatening than cold alone.

I plant lavender in raised beds or mounded soil to help prevent soggy roots. Pruning is important: after flowering, I trim lightly (avoiding cutting into old wood) to maintain compact form. In fall, I sometimes mulch just around the base (not over stems) for added insulation.

In winter, lavender may benefit from a light straw or evergreen bough mulch around the plant’s base—just enough to protect the crown without smothering air circulation. In spring, I remove that mulch gradually so shoots aren’t held back. Over time, lavender becomes a fragrant staple in my garden edges or herb patches.

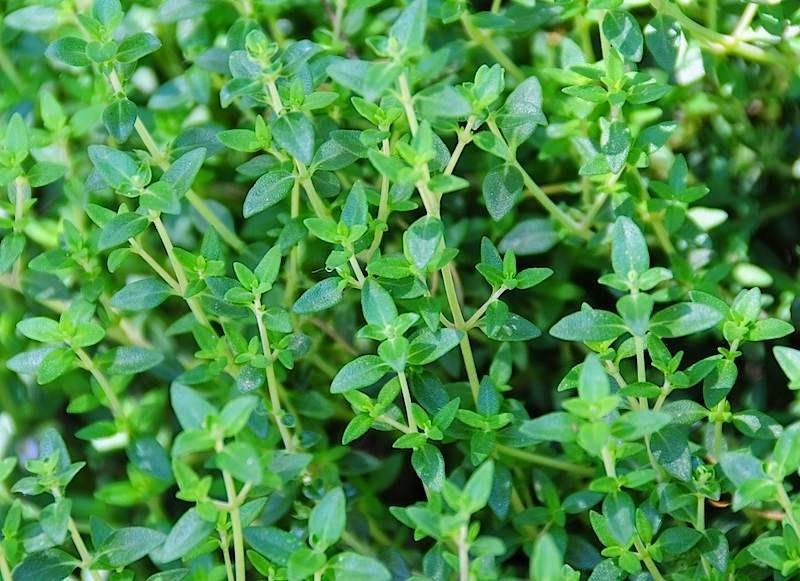

14. Thyme (English or Lemon Thyme)

Thyme is a hardy herb that does surprisingly well in Zone 6b with the right conditions. It enjoys full sun, well-drained soil, and occasional drought. I sometimes tuck thyme into rock gardens, between stepping stones, or at the edges of herb beds—places where moisture doesn’t linger.

It’s low fuss: I trim it after flowering to keep it tidy and to encourage fresh foliage. The aromatic leaves make it a fragrant companion to vegetables or perennials, and I often grow multiple thyme varieties (lemon, English, creeping) to layer scents and textures.

Winter-wise, thyme is generally hardy. I give it a light mulch to protect the crown, especially in places where snow may shift. In spring, I prune back any dead twigs, tidy the patch, and fertilize lightly. Over seasons, thyme tends to self-maintain without much intervention.

Seasonal Planting Calendar for Zone 6b

- Early Spring (March–April): Begin by preparing soil—test, amend, and mulch. Sow cool-season crops outdoors once soil is workable: lettuce, spinach, radishes, peas. You can also start some seeds indoors (tomatoes, peppers) in late April, hardening off just before last frost.

- Late Spring–Summer (May–July): After last frost, transplant warm-season crops like tomatoes, peppers, and annual flowers. Maintain watering, weeding, and pest control routines. Mid-summer, you may plant a second round of quicker crops or fill gaps in your flower beds. Begin fall-sowings of greens or root crops in late July or early August.

- Fall (August–October): Harvest summer crops before frost. Sow fall-hardy vegetables (spinach, kale, carrots). Plant perennials, shrubs, bulbs, and herbs—these will have time to establish before winter. Mulch beds and protect sensitive crowns. Keep an eye on frost forecasts; harvest any remaining tender produce and move container plants indoors if needed.

- Winter (November–February): Focus on cleanup, mulching, and dormant-season protection. Repair and sharpen tools, order seed catalogs, and plan next year’s layout. Remove snow from fragile branches if heavy, protect root zones from freeze-thaw cycles, and monitor for rodent or deer damage under snow cover.

·

Common Challenges in Zone 6b Gardening

A. Frost Damage

Early or late frost is always a lurking danger. I keep lightweight row covers, frost cloths, or old sheets handy so I can toss protection over plants when a surprise cold snap hits. For tender seedlings, temporary cold frames or cloches help. In fall, I sometimes move delicate containers indoors or wrap them overnight.

Certain plants (hydrangea buds, early blooms) are especially frost-sensitive. Timing and microclimate awareness help—plant those further from open cold air, perhaps closer to a south-facing wall or where a wind buffer exists. Pruning too early in spring or too late in fall can expose vulnerable growth to frost—so I time pruning carefully.

Also, leaving a handful of mature leaves or mulch can buffer young roots and crowns. I avoid exposing fresh, tender growth too early by waiting until danger of frost truly passes. That cautious patience usually saves me more grief than rushing to get everything planted.

B. Pests and Diseases

In Zone 6b, pests like aphids, slugs, tomato hornworms, and fungal diseases (powdery mildew, blight) often show up. I scout weekly, checking undersides of leaves and new growth. Early detection is key. For pests, handpicking, insecticidal soaps, or beneficial insects (ladybugs, lacewings) often help. For disease, I ensure air circulation (proper spacing, pruning), avoid overhead watering, and rotate crops.

Cleanliness helps: I remove diseased leaves, dead foliage, and debris in fall or spring to reduce overwintering pests. Also, I avoid planting the same family in the same spot year after year (e.g. tomatoes after tomatoes) to reduce soil-borne pathogens.

Using companion planting (e.g. marigolds near veggies) and interspersing flowers among crops can bolster beneficial insect presence, which in turn helps keep pests in check. Over time, your garden develops its own balance, but the first few seasons often demand extra vigilance.

C. Drought or Excess Rain

Spring in Zone 6b often brings excess moisture, while summer can swing to dryness. Too much water early can drown roots; too little later can stress plants. I rely on good drainage, raised beds, and mulching to buffer extremes. I also install rain gauges or moisture meters to avoid guessing.

During dry mid-summer stretches, I water deeply but infrequently, encouraging roots to go deeper. I avoid surface watering or light daily sprays. If drought lingers, I may use shade cloth temporarily or mulch thicker to reduce soil temperature and moisture loss.

Conversely, when heavy rains persist, I check that beds aren’t staying saturated too long. Sometimes I open pathways for drainage, avoid walking compacted soil, or even create French drains in extreme wet spots. The goal is balance: let your garden breathe, not drown.

Wrap Up

I’ve watched my garden evolve over years—patches that once failed now flourish because I picked the right species, learned to time plantings, and built soil that supports resilience. Zone 6b presents both challenges and opportunities: winters cold enough to test plants, summers warm enough to encourage lush growth.

By focusing on a reliable list of 14 plants—flowers, vegetables, shrubs, perennials, and herbs—you give your garden a framework of dependability. These are plants I’d plant myself, ones that survive cold winters, tolerate summer shifts, and still reward you with blooms, fruit, fragrance, or structure.

Your garden will have surprises: some plants will thrive beyond expectation, others may falter in microclimates you didn’t anticipate. But with thoughtful planting, soil care, and seasonal awareness, you’ll be setting up your space to succeed—year after year. Let me know when you’re ready to pair these with layout ideas, companion planting suggestions, or visual guides!